I have two young children. Like any parent, I am excited to see them grow up and to share the things I love with them. I’m excited to read them The Wind and the Willows and Harry Potter. I’m excited to eat lobster rolls with a Maine lighthouse in the background on a future family vacation. And I’m excited to play catch and take them to the ballpark to catch a game.

But should I share with them my love of the Chicago White Sox?

I teach ethics and introductory philosophy to college students. So, I’d frame the question this way: Is it moral to raise a child to be a White Sox fan?

To any White Sox fan, it’s obvious why this is even a question. In brief, White Sox fandom is pain.

To make matters worse, I didn’t inherit this particular disease. I chose it. As a native Kentuckian, I had no ties to the Sox. As fate would have it, I was placed on the “White Sox” as a 7-year-old — just about the time I took an interest in Major League Baseball and baseball cards. I started collecting White Sox baseball cards because why not? I was a White Sox player! And they had the most fearsome slugger of the day: the Big Hurt, Frank Thomas.

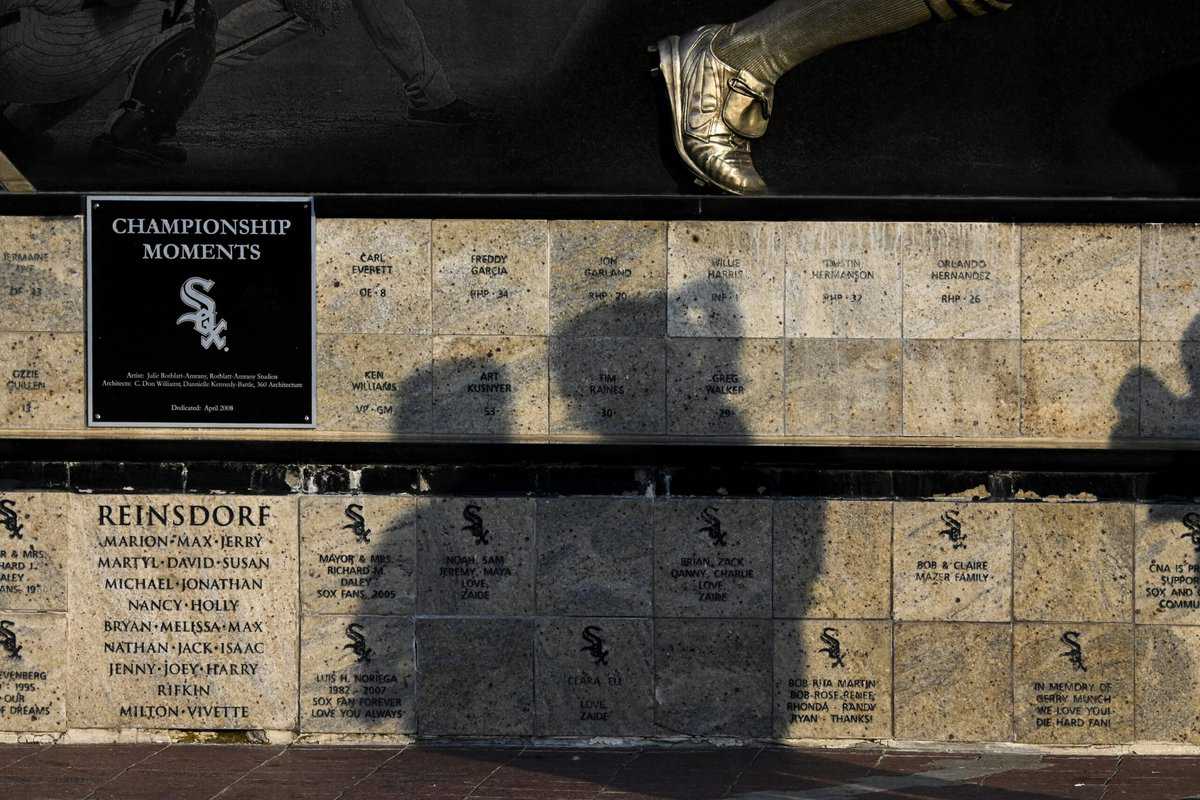

The Big Hurt became my favorite player. It wasn’t long before I had a life-sized cutout of him in my room (who often startled visitors who caught a glimpse of a bat-wielding Frank in their peripherals while walking down the hall). Watching Frank hit was fun. And the good times got better in early high school, when the Sox won their first World Series in, well, a while. I had picked my favorite team well.

Poor, sweet, innocent, 15-year-old me.

I’ve sometimes wondered what my today-self would tell my 7-year-old-self if I could rewind the clock. With my sage wisdom and depth of insight from my experience, would I talk myself out of it? “Be a Cardinals fan,” I can imagine myself saying. “Your dad is a Cardinals fan. St. Louis is closer to home. And things will go so. much. better.”

Alas, we don’t get to rewind the clock. I am a White Sox fan. It’s too late for me now. I can no more abandon this team than I could oxygen.

But it’s not too late for my progeny.

Since 2005, the franchise I love has been mostly a steaming pile of garbage, aside from the occasional waft of an decent-smelling flower. With an owner who seems hell-bent on disappointing fans and living forever, the future is not exactly bright. Should I initiate my son into this? Is it even moral to do so?

To explore this further, let’s try to mount a philosophical argument against sharing my fandom with my son. The general idea is this: It’s immoral to pass things onto our children that will cause them suffering. If we turn this into a formal philosophical argument (or a “syllogism”), we get:

Premise 1: If you know doing something will cause your child suffering and pain, you should not do it.

Premise 2: I know teaching my son to be a White Sox fan will cause him suffering and pain.

Conclusion: Therefore, I should not teach my son to be a White Sox fan.

That’s the argument. The argument structure is valid. But are the premises sound?

In philosophy we teach our students to question everything. And to be precise. As is, Premise 2 is vulnerable. It’s a little too strong. The fact is, I don’t know teaching my son to be a White Sox will cause him suffering and pain. After all, Chris Getz might be the best GM ever! This next rebuild could permanently turn things around! The Sox could be the Dodgers of the future!

But once we’ve come down off this brief acid trip, we can save the argument by making the argument a little more modest. Let’s try this alternative version:

Premise 1: If you have good reason to believe doing something will cause your child suffering and pain, you should not do it.

Premise 2: I have good reason to believe teaching my son to be a White Sox fan will cause him suffering and pain.

Conclusion: Therefore, I should not teach my son to be a White Sox fan.

Now we’re cooking with gas.

Premise 2 is now reasonable and, frankly, difficult to deny. But does the argument hold up?

It initially seems strong. But what about Premise 1? Like 2021 Tim Anderson, it’s the straw that stirs the drink. Premise 1 articulates the basic intuition that makes us ask this question in the first place. But, philosophically speaking, is it sound? Should we accept this assumption?

Some philosophers would say yes. Most notably, Epicurus — and his followers, creatively-called Epicureans — thought the meaning of life was found in simple pleasures and avoiding pain. If avoiding pain is our North Star, then Premise 1 has momentum. If you want to be a thorough-going Epicurean, you might have a good case to keep your kid away from the White Sox.

However, most philosophers — and most of our moral intuitions — don’t buy Epicureanism. Aristotle, for example, thought the goal of life was to become virtuous, a path that usually, if not necessarily, involved struggle and pain. Or in the immortal words of the modern athlete, “no pain, no gain.” For philosophers before and after Aristotle, pain and suffering have played a critical role in shaping us. C. S. Lewis called them “teachers” — we often learn the most from the difficult parts of life.

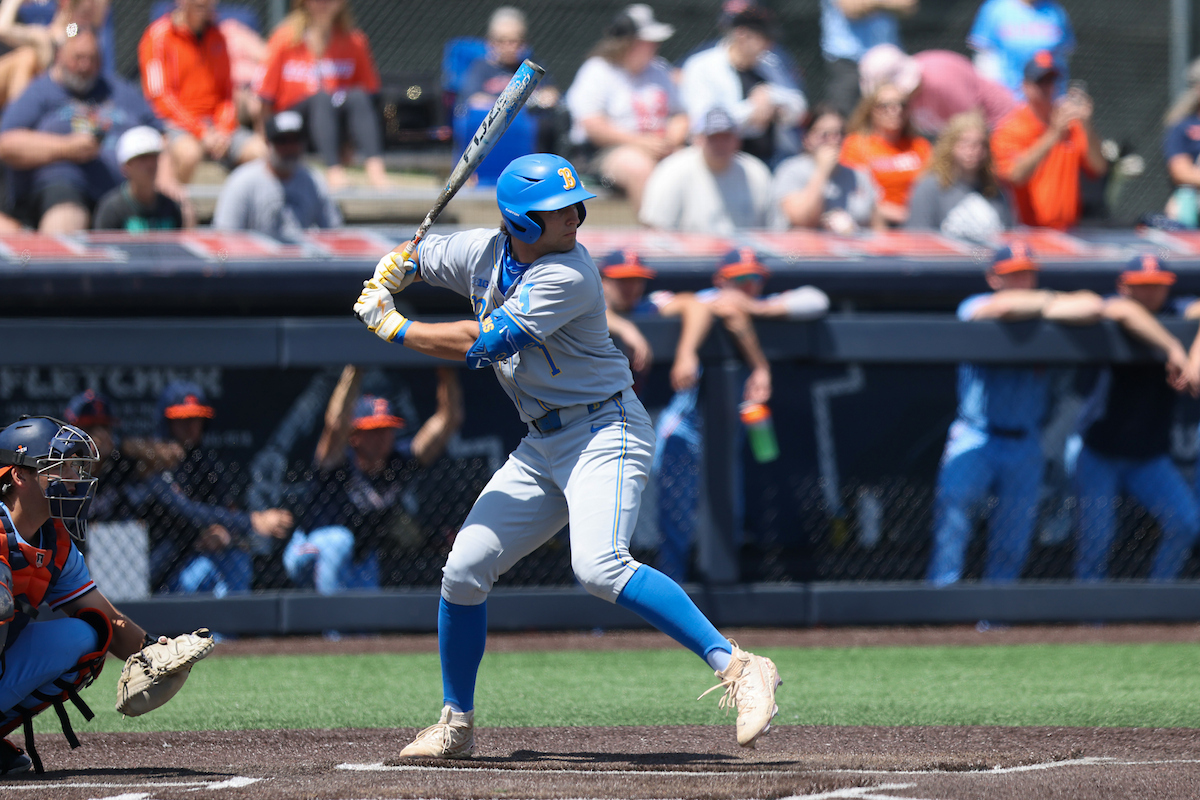

We may not have a tidy philosophical system, but in practice most parents reject Premise 1. We often put our kids in situations even when it’s likely they’ll experience pain. I let my kid run on the playground even though I know it will likely result in pain of some kind, like a bonked head or a scraped leg or a hurt ego. When I inevitably sign my son up for Little League, I can all but guarantee that it will cause him pain. He’ll get hit by the ball. He’ll collide with another player. I was a catcher 15 years ago and I still haven’t recovered full feeling in my right wrist. But playing baseball also causes emotional pain. He’ll almost certainly be embarrassed, ashamed, or sad because of baseball at some point. As parents, we allow all these things. We allow them not only because it allows other, better feelings, but because they teach us a little bit about how to be a person and face life.

If all that’s right, Premise 1 is in trouble. But notice: the examples of allowing my kids suffering always include some other goods. I don’t let my kids suffer just because. I have to have some other reason. Some greater good that makes the pain worth it. Can being a White Sox fan be worth the pain?

Being a fan of a team, like playing on a team, does offer several goods. Wins come with the losses. There’s community (as evidenced by the good folks here on Sox Machine). And as ridiculous as it sounds, I truly believe being a Sox fan builds character.

But you get all those things with any team. Why the White Sox? What does this team have for my son that others don’t?

There’s an argument out there that the answer to this question is “The writing of James Fegan and Jim Margalus” but I won’t explore that answer here. I’ll try another. This team has something that no other MLB team has: me.

Through all the heartbreak seasons, we sometimes forget that baseball is a game for our enjoyment. And like any entertainment, it’s best when we share it with the people we love. If I raise my child as anything other than a White Sox fan, I’m depriving him of opportunities for more bonding with his dad. One of the best things about being a parent is sharing things we love with our kids, but it’s also one of the best things about being a kid. I have fond memories of hearing about the things my dad cared about. I still care about some of them. Not all. But they all shaped me, and I saw through them how he cared for me.

If I can give my kid that through the White Sox, then I would say: Yes, it’s moral to raise your child to be a White Sox fan. I’ll just hope, in the meantime, there’s a little less pain and suffering in store for him.