Even when your work is behind a paywall, if you do this job for long enough, people start to identify what kind of stories you write. So it was unsurprising the other day to have a -- non-baseball operations -- White Sox employee lean in and ask:

"Have you figured out why they're hitting fastballs now?"

Per Statcast's weighted run values for performance against pitch types, the White Sox are still the fourth-worst offense in MLB against fastballs for the season. But that only drives home how much their post-All-Star break run production (7.3 runs per game, .289/.342/.511) has seen them flip a switch, where they've been the second-most potent fastball-hitting team in baseball over the first three series of the second half.

In lieu of some granular mechanical breakdown of how 13 different hitters have all contributed to this larger trend, the leading explanation is that the Sox are hitting fastballs because they were told to -- forcefully, repeatedly, with emphasis.

"That’s what we’ve been pounding our fists on the table for all year here," said Will Venable.

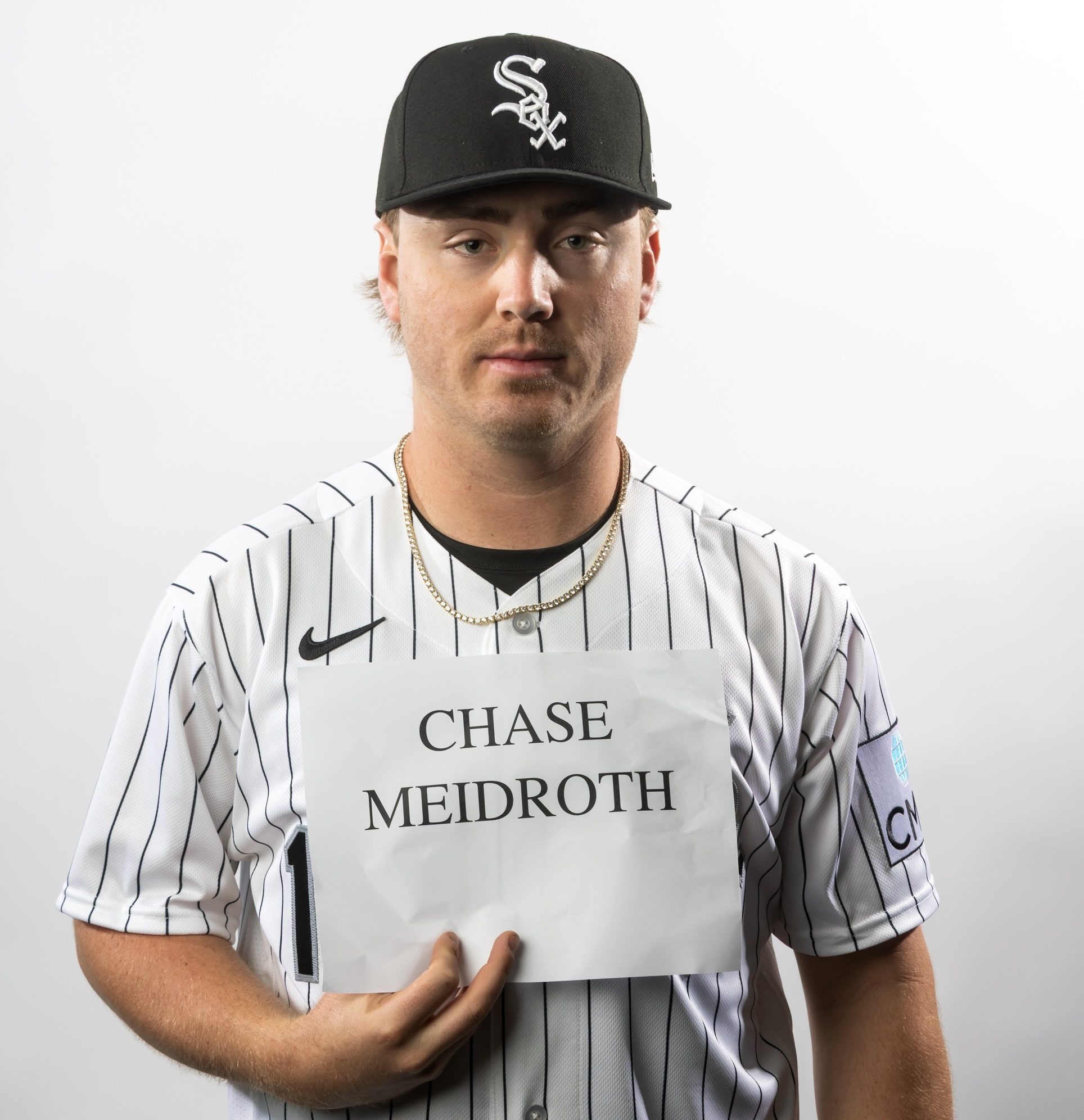

"We've talked about being more aggressive on fastballs and I think we've come out and done that," said Chase Meidroth. "If the ball is thrown over the middle we're going to put a good swing on it and get our A-swing off, and if not, we're OK taking a walk and giving it to the next guy."

"It’s really hard in this game if you are not competitive with the fastball, especially in the heart of the plate," said Mike Tauchman. "Guys throw hard. You have to be ready to go. And you know, we have a lot of guys who control the zone. The next step in that is controlling the zone but being aggressive to your pitch."

As the result of a similarly great amount of focus and effort, the White Sox have been a more patient offense this year than this franchise has fielded in over a decade. Their rate at swinging at pitches out of the zone has been in the bottom-third of the league all year. They simultaneously have the eighth-lowest chase rate and the 12th-highest walk rate, but the notion that this newfound patient approach has led to the influx of fastballs in the zone from opposing teams is up for debate.

Maybe it's a terminal case of competitive athlete brain, but most Sox hitters are just as quick to frame the fastballs they've seen as a product of not mashing them enough, as they are to see it as something their patience has earned. To their point, the Sox saw the third-highest rate of four-seamers in the first half (34 percent) and in response to how poorly they hit them, the Pirates, Rays and Cubs have ratcheted it up to a league-leading figure (41.7 percent) since the break.

"I just don't think we performed very well against fastballs the first half of the season," said Austin Slater. "I don't know if that's necessarily the playbook anymore in the game. In baseball in 2025, I think pitchers are still gonna spin you in hitter's counts more than they ever have. But I think if a pitching staff were to look at our team in the first half, I think they would feel good about attacking us with fastballs."

"The death of fastball performance is getting caught in between," Michael. A. Taylor said. "Doing damage on heaters kind of makes teams not want to throw you fastballs. Maybe it's a product of being so selective and not really slugging fastballs earlier in the season is why we're getting fastballs at this part of the year."

Ultimately, ultra-vigilant fastball production is supposed to work symbiotically with good swing decisions, and drive opposing pitchers to nibble around the zone, leading to walks. But that's more of a long-term effect than an immediate assurance when hitters are gearing themselves up to try to pull fastballs.

Because while the arrival of Colson Montgomery will help to start tipping the scales a tad, the White Sox are still dead-last in average bat speed per Statcast, after being 28th last year. They do not have make-up speed when it comes to jumping on velocity. It requires a leap of faith.

"We watch video, we know the repertoire of the pitcher and we have a game plan, and for me it's just about being convicted," said hitting coach Marcus Thames. "If I'm saying I'm going to be on the heater, I can't be in-between. If your mindset is to be on the fastball and you chase a changeup, you've got be OK with it, because you're on time [with the fastball]. It's being convicted with what you say you're going to do."

"Swinging through a pitch early in the count is not the worst thing, because you've got two more, and you've just got to be OK with it," said Benintendi, hours before he pulled two early-count fastballs for homers on Sunday. "I think it's more about mentality. Instead of trying to stay inside a fastball and going the other way, it's being ready to turn on it. Driving stuff to the pullside gap on a heater opens up a lot of other stuff too, so it's just being more committed to doing that."

This entire saga resides firmly in the territory of easier said than done, where a roster that generally lacks the raw bat speed to thrive against heaters organically is straining to account for those deficiencies with their approach. The team is also heavy on rookies and hitters getting their first full-season as big league regulars, and swimming through the challenges of adjusting to top-level pitching often runs counter to disciplined commitment to fastball timing and shrugging off any consequences.

Thames points out that it's easier to understand the flip in the context of the full season rather than just the team meeting the Friday after the All-Star break. The same infrastructure that pumps out biomechanical reports informing when Miguel Vargas' hand placement is sliding out of place has been churning reports for months telling players about their sub-standard fastball performance.

It's been the headlining topic of plenty of hitters meetings prior to the Pittsburgh series. Sacrificing their pristine plate discipline, risking strikeouts, all become acceptable in the face of addressing a .344 slugging percentage and the third-fewest runs scored in the first half. Maybe this is just another fold in the cat-and-mouse game, and teams will soon pivot to a offspeed-heavy attack in response to the Sox offense. After all, they're not even executing the biggest flip in their division: the Guardians were the second-worst offense in MLB against fastballs in the first half per Statcast run values, are now they are the only team hitting velocity better than the Sox since the break.

Even so, it was still a necessary pivot. Both because the offensive status quo was unacceptable for the Sox, and their collective response to coaching emphasis bodes well for future challenges.

"It's just been great to see and listen to the guys in the dugout, in the cage, in our meetings really being convicted on that we've got to get better at it," Thames said. "As a whole, as a collective, as a group, everybody's committed."

As Slater said, baseball in 2025 features fewer fastballs than ever. But the only view to a sustainable operation includes closing off fastballs in the zone as a viable option for opposing pitchers.

"I want to stay on the fastball, so when usage kind of swings the other direction, my thought is just shrinking the zone," Taylor said. "Honestly at times, I'll tip my cap if they land a slider or changeup at the bottom of the zone, but I don't want to put myself in-between by wanting to cover those pitches, and then I'm late on fastballs. So I try to eliminate that cat-and-mouse by just sticking to my approach and trust in the fact that if I'm aggressive in my zone, I'll get enough pitches to hit without trying to."

This is all an aberrant nine-game stretch at this point, and running into a team that's not actively on the skids this weekend stalled a good degree of the offensive momentum. But part of buying into the White Sox's current state is not viewing them as aimlessly riding the brief highs and sustained lows of another rebuilding season, but accumulating skills on an upward trajectory toward contention.

In this view, even a small burst of fastball production is the culmination of months of focused work. Suggesting something even seemingly innocent as their young players, navigating the rigors of a big league season for the first time, have been rejuvenated by the respite of the All-Star break gets a decidedly mixed reception.

"It was, whatever, two days off, but the whole time I was thinking about getting back and getting ready to compete in the second half," said Meidroth.

Dang man, do you even look forward to off days?

"No, not until the offseason."