There's no meet-cute story about Texas A&M head baseball coach Michael Earley first seeing Braden Montgomery, no anecdote about uncovering a diamond in the rough. If the newly acquired White Sox prospect wasn't already universally known around the college recruiting world as an elite two-way prep talent, Earley got even more familiar with Montgomery in 2023, when he helped end the Aggies season with a monster offensive performance in regionals as a sophomore still starring for Stanford.

When Montgomery's services came available afterward, Earley was just one of many interested suitors.

"Him going in the portal was obviously not only on our radar, but on everyone in the country's radar," Earley said by phone. "You got to see first-hand what he could do. And then we were able to land him, which was obviously huge for our program."

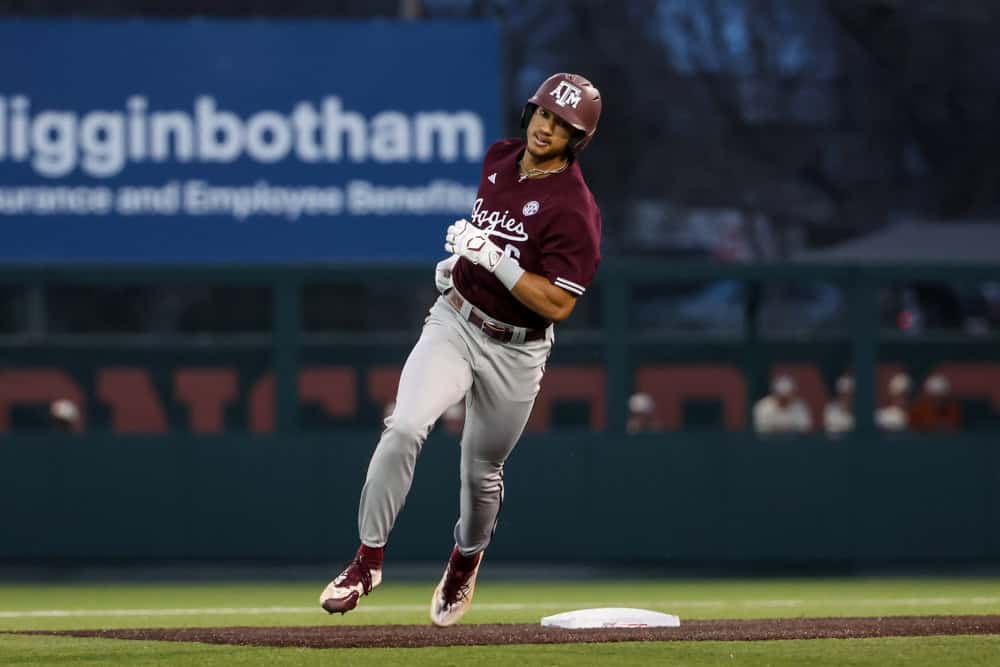

A former White Sox farmhand himself, Earley served as the Texas A&M hitting coach for Montgomery's lone season in College Station this past summer. And because the fractured ankle Montgomery suffered during super regionals in June postponed his professional debut, Earley oversaw the last game action of the new top-rated outfield prospect in the Sox system.

Montgomery's OPS already cracked four-digits as a sophomore at Stanford, his strikeout and walk rates stayed mostly static--albeit against superior SEC competition--in his draft year at A&M, and Earley doesn't testify to orchestrating to any big mechanical overhaul. He also doesn't hesitate to share that a big part of why Montgomery came to the Aggies is because his personal hitting coach, Jeremy Isenhower of Premier Baseball, is located outside of nearby Tomball, Texas and Earley had no issues with being part of a group effort.

But Earley's simple approach to facilitating a junior year that saw Montgomery hit .322/.454/.733 with 27 homers in 61 games, is fairly similar to the challenge awaiting the White Sox player development staff with a prospect who was regularly striking out 20 percent of the time in college. Montgomery's raw power and athleticism suggests star potential, but accessing that ceiling is dependent upon putting more balls in play.

"In my opinion, Texas, A&M has been the best, if not one of the best, controlling the strike zone teams in the country," Earley said. "We try to get guys out of the portal we feel like we can make better just by controlling the zone. He obviously showed the ability, his batted ball data is really good. So when he hits the ball, it hits it really well, hits it really hard. It was just about, really swinging the bat less and taking more balls and swinging at more strikes, so that's what he really made major improvements on."

Earley is still pining for the day that A&M gets their own Trajekt pitching machines that have become the rage in MLB, are set to become a part of the White Sox process, and provide a view of opposing pitcher arm action. But a college team having an iPitch machine that can replicate in-game velocity, spin and movement is still pretty fancy, and Montgomery's season of drilling down on pitches he could drive for power came alongside his voracious appetite for high-speed training.

"He was honestly to the point where there were times where I had to slow him down because I thought he was doing too much," said Earley, who noticed Montgomery had taken to programming his own sessions on the iPitch. "He likes challenge. He wasn't a guy that would come in and spend a lot of time hitting off the tee or front toss. It was a couple of rounds of front toss and he wanted to get into it. I thought that was super unique, because sometimes you run into guys where they don't like to get uncomfortable. They like what I call 'the feel-good hitting,' and with Braden, it was great. Honestly, him being one of our best players, him wanting to do stuff like that fed our entire team."

The glass half-empty view--one never dismissed around these parts given what we have all witnessed--is that the leap in strike zone discipline that could be expected by exposing Montgomery to professional-level training technology has already taken place at an elite SEC program. He unquestionably got a lot better at teasing out pitches he could crush, launching himself to be the 12th overall pick this July despite injury, but long-term questions about Montgomery's hit tool remain and he still struck out more as a junior than elite MLB hitters typically do in college.

A rosier outlook would be that Montgomery has already shown comfort with the advanced tech, long hours and the willingness to learn from failure that will become a prerequisite for thriving in pro ball. And if he's responsive to ways to cut his out-of-zone chasing, Montgomery's raw physical ingredients have always suggested he can be a force inside of it.

"It's elite bat speed and rotational acceleration, his body and the way the bat moves through the zone with his core strength is as fast--if not the fastest--as I've ever coached," Earley said. "Which at time I think can get him in trouble, because you can move too fast. And if you go in the wrong direction moving too fast, it's even more trouble. But that thing moves. The torque and the quickness of it, it's kind of hard to explain. It's really fun to watch. His ability to hit the riding fastball, like elite ride heaters at the top of zone, it's better than anyone I've ever coached and better than anyone I've ever seen. He got to a couple pitches that were actually balls above the zone on real, metrically graded heaters and hit some homers. It's just that ability for the body to move super quick in the right direction."

This level of proficiency is seen more in Montgomery's left-handed swing, with Earley opining that more exposure to left-handed pitching is necessary to get his right-handed cut up to snuff, since the bat speed is similar. And the proliferation of spin across the professional game has diluted the old adage that hitters just need to be timed up to handle the best fastball the opposing pitcher can throw. But it does form Montgomery's offensive identity as a hitter that will rarely be overpowered, and whose success is largely predicated on how much he can stave off attacks from off-speed offerings.

Having already witnessed Montgomery proactively decide to challenge himself with better competition and rise to its requirements, and how much his genial outward demeanor contains an ultra-serious perfectionist within, Earley sees him as someone who has already shown the ability to make a big leap in response to big expectations.

It's just that his biggest challenge yet is still coming.

"The game's changing on pitch usage and stuff, but I've got to imagine you've got to be able to hit fastballs and that is something he can really, really do," Earley said. "He hit off-speed stuff too, but it was more he did a really good job with the off-speed pitches that he laid off and that really was what defined his season. I think he's in a really good spot and I think you guys are getting an unbelievable athlete, and a worker that has a chance to be a star."