The White Sox laid an egg against the Kansas City Royals last night. A pitching matchup that looked advantageous on paper didn't materialize on the field. Lucas Giolito gave up three homers over four innings, while Carlos Hernandez stymied the Sox for the second time in two weeks. The Royals won 9-1. It might not have been that close.

After the game, Tony La Russa sounded inclined to write off the performance.

"I think a guy goes out there 30-some times, you are going to have a game like that where you are just not right," White Sox manager Tony La Russa said. "You are going to have several, just the way (it goes). You are a man, not a machine.

"You go out there as a starter all year long, and you are going to have games (like this). ... Just a little bit like Carlos the other day in Kansas City. Early on they get you, and before you are right, it’s not your day."

And there's good reason. Giolito's season has been a disappointment relative to preseason expectations where ZiPS projected him the best pitcher in baseball, but he entered the game with a 3.02 ERA over his previous 13 starts and remained on track for an above-average season despite the occasional jarring speed bump. He didn't have a breaking ball worth respect, and a contact-oriented lineup landed jabs and haymakers. "It happens" is an unsatisfactory excuse, but it's understandable.

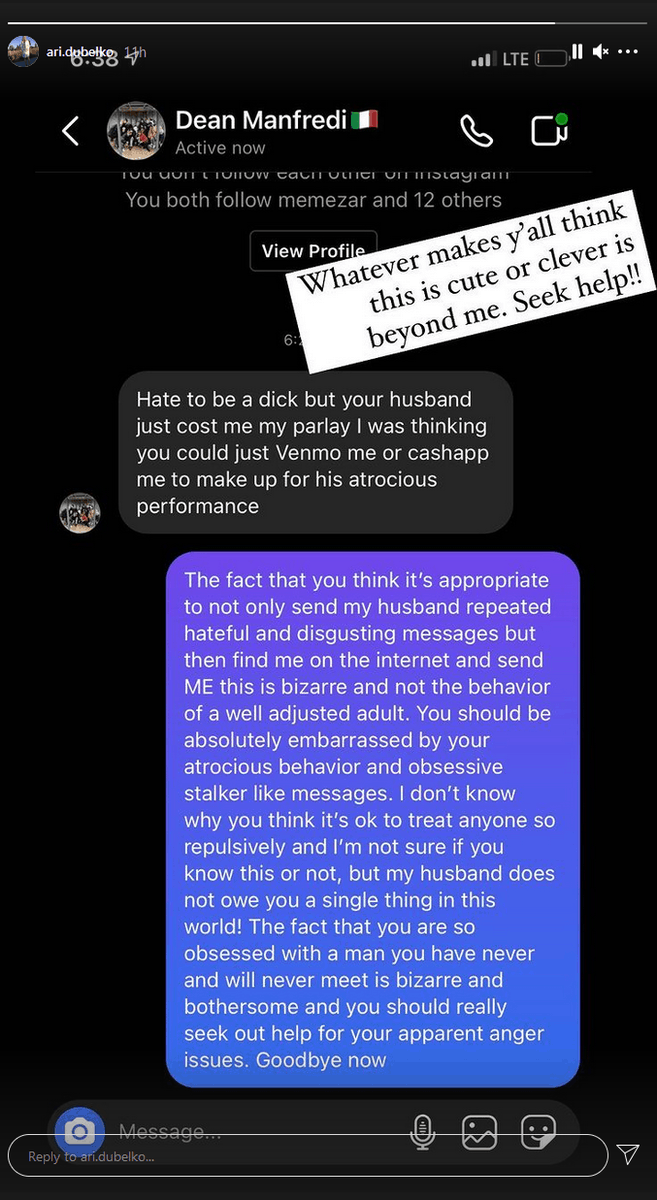

The excuse appears to be even more unsatisfying when you have money on the game, and apparently Wednesday's "upset" led to some responses that are beyond comprehension.

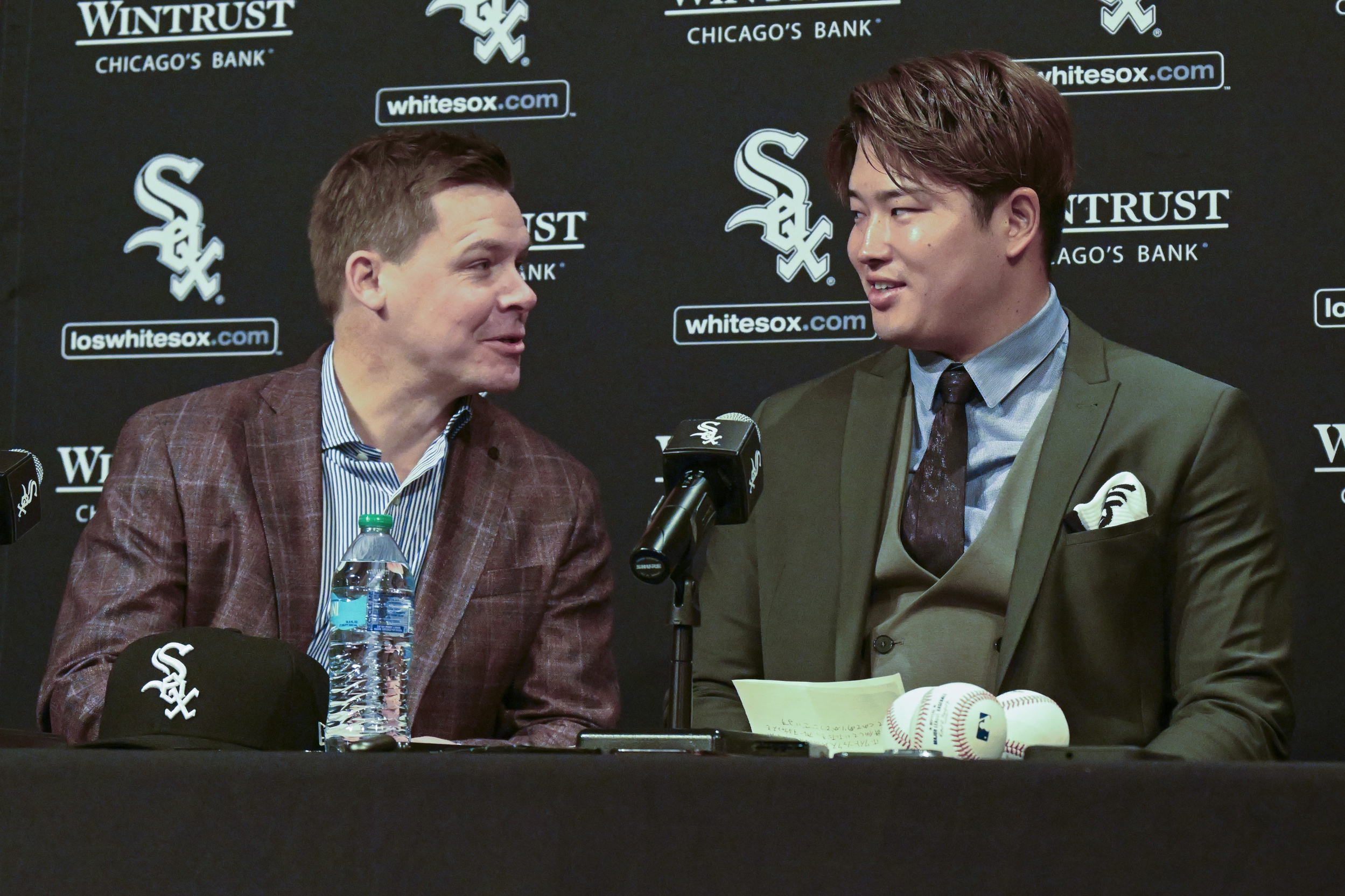

During the game, Ari Dubelko Giolito, Lucas Giolito's wife, shared an exchange from her Instagram account.

After the game, Zack Collins, who was behind the plate for Giolito's dud, alluded to even harsher messages.

This is not the first time the outcome of a recent White Sox game generated unhinged responses from the public, or at least the portion that had money riding on the proceedings. In June, a 24-year-old Californian was sentenced to probation after pleading guilty to issuing threats to one White Sox player and four Tampa Bay Rays after the Sox won a game at Tropicana Field in July 2019.

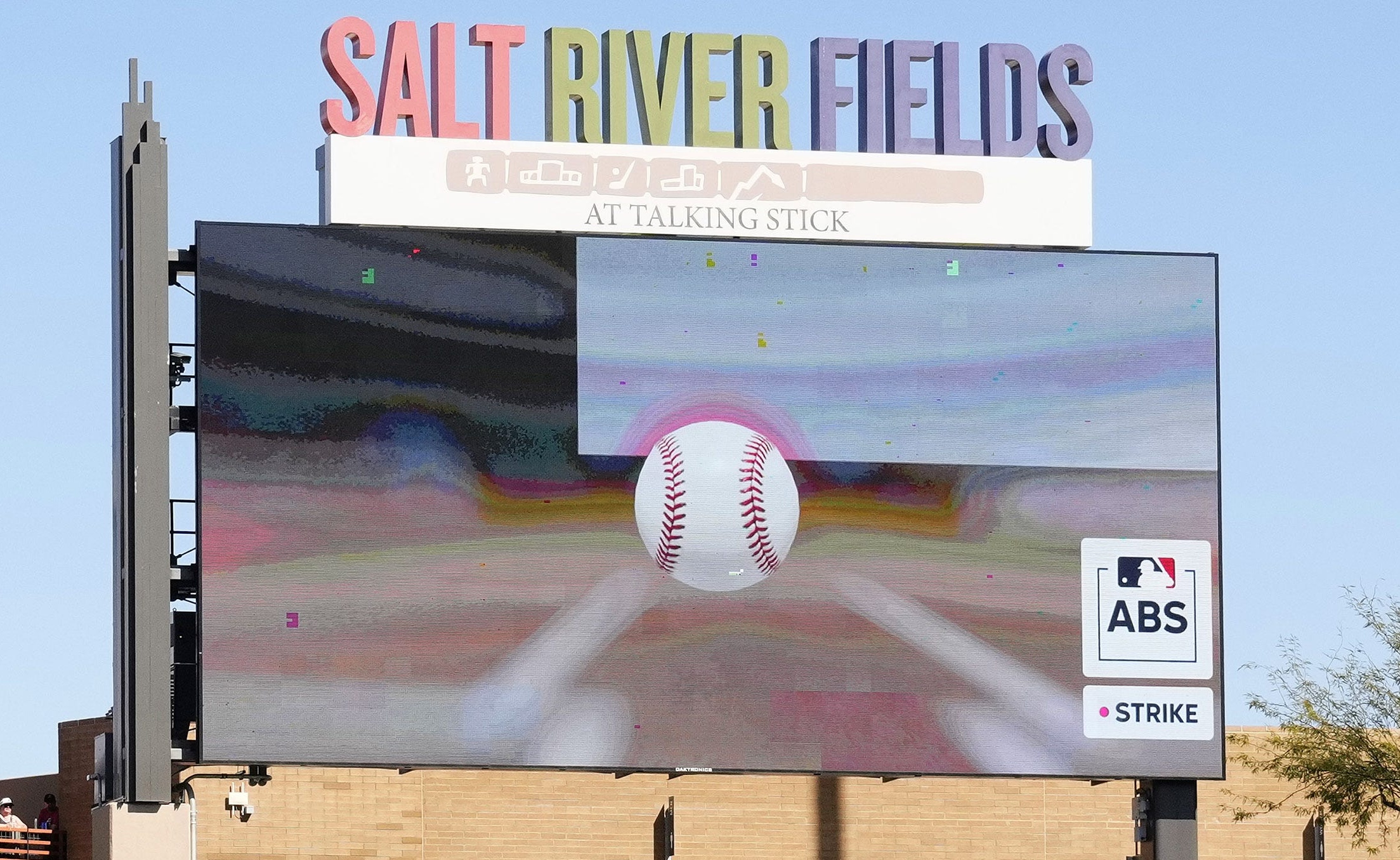

I'd say I'm baffled by the rise of casinos partnering with Major League Baseball and other professional sports, except the money is the kind that overrides objections. But I am confused about the ease that it's been accepted, mostly because a childhood spent learning about White Sox history suggested that gambling was a poisonous influence on sports to be avoided at all costs.

* * * * * * * * *

With sublime timing, the Society for American Baseball Research this morning unveiled a review of the 1921 season as told through six stories. One of them centers on the trial of Black Sox, which turned 100 last week. Black Sox scandal expert Jacob Pomrenke used his Twitter account to relay daily accounts of the trial, which resulted in the acquittal of the eight White Sox players accused of throwing the 1919 World Series, but didn't prevent Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis from banishing them from Major League Baseball regardless.

The reasons people sympathize with the Eight Men Out are largely rooted in myth, or at least a lack of context. Charles Comiskey tried to avoid paying his players more than he had to, but the same could be said of every owner, because players possessed near-zero leverage. The White Sox might've been underpaid relative to their drawing power, but they were paid well relative to the rest of the league.

If there's any reason to defend them, it's that baseball turned a blind eye toward gambling for years, and even the Black Sox for a while. Pomrenke describes the setting:

Gambling in baseball was a hot-button issue in the early 20th century, just as it is now in the 21st century. Landis was hired by major-league owners with a mandate to clean up a corrupt game. Before the 1919 World Series scandal erupted, players and front-office executives were known to openly bet on their own teams (both for and against) and bettors were allowed to operate freely in major-league ballparks. Fans could attend a game at Wrigley Field in Chicago or Fenway Park in Boston and place a bet on the next pitch from their seat — a scenario that would not look out of place at a ballpark in 2021, given the growing world of legalized sports gambling.

My day-to-day recap of the 1917 White Sox's championship season included a game at Fenway Park that was interrupted by gamblers who rioted in an attempt to prevent the game from becoming official. Such an embarrassing incident could have prompted a league-wide reassessment of its ties to gambling, but leadership instead kicked the can until gambling infected the integrity of a championship.

In another instance of impeccable timing, on the same day you can read Pomrenke noting that gambling at Wrigley Field would not look out of place in 2021, the Cubs are officially proposing plans for a two-story addition on their ballpark in order to house a sportsbook.

All the elements that led sports to distance themselves from gambling a century ago seem to be forming a storm that'll lead to the exact same disasters. The NHL is currently investigating accusations that Evander Kane of the San Jose Sharks bet on hockey and compromised games for gambling purposes. Kane has denied the charges, but they have some heft because 1) they're coming from his wife, and 2) Kane filed for bankruptcy earlier this year because of a gambling issue.

Whether he bet on his own sport or merely has an unrelated addiction, Kane earned $6 million in 2021 and has made nearly $56 million in his career according to CapFriendly. Theoretically, he shouldn't be hard-up for cash the way Eddie Cicotte overextended himself with a $4,000 farm mortgage on an $8,000 salary. Yet here we are.

The comfort with which the leagues and media outlets have partnered with sportsbooks makes it hard to determine an appropriate level of alarm, because they were the bulwarks against gambling's influence on sports until they suddenly weren't. Who watches the watchmen now? If it's up to individuals, here's one noting that the elements baseball spent a century beating back seem to be all present, wondering if anybody took care of the "accounted for" part.

Once you're done mulling over that question, check out the White Sox's promotion of next Thursday's Field of Dreams Game, in which they wear the uniforms made famous by ... well, you know.

(Photo of the 1919 White Sox from the George Grantham Bain Collection / Library of Congress)