White Sox third-round pick Kyle Lodise was described by his head coach at Georgia Tech, the renowned Danny Hall, as a late bloomer. Retiring this season after over 1,400 career wins, Hall went on to reveal that he hadn't even heard of Lodise, who compiled a nearly 1.100 OPS for the Yellow Jackets as junior, until his staff began assessing their options in the transfer portal.

Lodise would argue that both he and his cousin Alex, drafted by the Braves out of Florida State a round earlier this July, were "under-recruited" coming out of high school and weren't on the radar of ACC programs until they thrived elsewhere. But he also doesn't refute his coach's assessment.

"Growing up I was super small, I really didn't get that big growth spurt until my sophomore year of high school, going into junior year," Lodise said. "But I think it's honestly been a blessing because it's allowed me to become really self-aware in that timeframe and being able to learn my body."

Now listed at a spry and possibly generous 5'11" and 180 pounds, Lodise's first blush with professional baseball has him determined to head into the offseason with the goal of adding 15-20 pounds of strength to handle the physical demands of his new workload.

"He is undersized right now," said director of hitting Ryan Fuller. "Being able to take this opportunity of the offseason, come to Arizona, work with us, get stronger going into next year, and being able to withstand an entire season will be a huge key for him, because he does showcase the ability of good swing decisions, good contact, and now it's being able to hit the ball hard enough that it's going through the gaps."

After getting the most aggressive assignment of any 2025 White Sox draftee and producing an effective but unglamorous High-A batting line (.185/.319/.370 is a 108 wRC+ in the South Atlantic League), Lodise finds adjusting to the grind of daily games to be similar to adjusting to the pitch clock. The moments to stop and think through what's happening are reduced. And it's both easier to maintain a groove, and also much easier to sink into a spiral.

Case in point, Lodise went 8-for-14 with three homers, five walks, three stolen bases and no strikeouts in a late August series against Wilmington, showing off both his advanced contact skills and the pull power he lacked until his later development. He followed up that South Atlantic League Player of the Week-worthy performance by going 2-for-23 with a double the following series in Rome.

"There's a lot to learn on, a lot to improve on," Lodise said. "I think I did a great job acclimating to the professional setting and stuff like that. The biggest thing moving forward next year, is just being able to flush bad games and learn how to be more consistent with routine and process."

But for this task, and most others in front of him in baseball, Lodise thinks that being a late bloomer will be to his benefit.

Growing up Yankees fans, Kyle, his cousin Alex and his younger brother Jordan all aspired to be shortstops because of their admiration for Derek Jeter. Mimicking his actions before possessing the physical capabilities meant that Lodise became practiced at "playing downhill," cutting the distance between himself and first base through every play, and using long bounces for throws across the diamond before he ever developed shortstop-quality arm strength.

Even with the White Sox drafting shortstops every other round these days, he wants to stay at the position, and it's a good sign for Lodise that he played there exclusively on a Dash team that had Caleb Bonemer, Jeral Perez and Ryan Burrowes on the roster. But like his new organization, Lodise rationalizes that playing short will also leave him well-prepared for different positions should he ever be asked to move.

"The beautiful thing about shortstops is they're super-flexible in the long term, because it's such a hard position that requires so many unique skills," Lodise said. "Being a little bit of a later bloomer than a lot of guys bigger, stronger, faster than you in high school, you're getting all this maturity as time goes on, figuring out how to do things when you're behind the curve. And then once you catch up physically, it makes it a lot easier to slingshot yourself ahead."

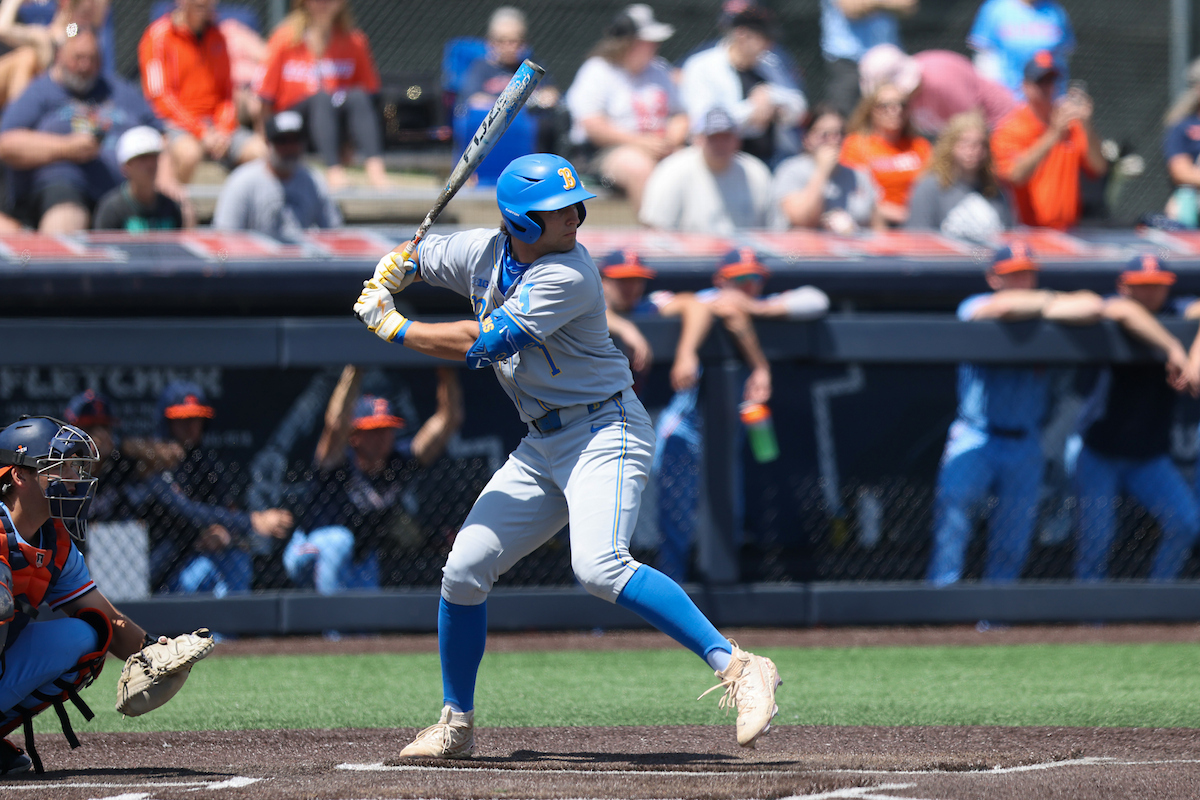

This principle applies also to Lodise's compact and quiet right-handed swing, which looks like it's already been put through the simplification process that many new draftees undergo in pro ball, because it effectively has. He shaved down his leg kick upon arriving at Georgia Tech this past season after two years at Division II Augusta, and now his stroke resembles that of most contact hitters, with minimal loading actions on his upper and lower halves.

But Lodise counters that his newfound feel for backspinning balls to the pull side emerged as the result of these alterations, producing 20 homers in 83 games this year when combining his time at Georgia Tech and Winston-Salem. Some necessary length in his swing is hiding in plain sight simply with how far away from his head he sets up his hands, another recent alteration.

"My hands are kind of my saving grace," Lodise said. "It's just allowing them to load naturally and get to a spot where I can hit from is what I really value, and just having space. I used to have them super close to my head, super tight, and I would run out of space, pin my arm to my back side. It would cause a lot of problems. That was one of the other things we really worked on, is how can we maximize my hands being as good as they are and as quick as they are? How can we let them work without any restraints? So that kind of loading move you see is just something that allows me to add some length out front to be able to bash the ball pull side with power."

Lodise said that he had three college scholarship offers out of high school, a personal fact he reels off with the readiness of someone who has already repurposed it as part of their own underdog narrative. But with the hindsight that a $922,500 draft bonus can only help fortify, the 21-year-old reasons he wound up getting a better opportunity from transferring than he would have by slowly working his way up the depth chart of a powerhouse program.

Between two years of starting everyday at Augusta, one year at Georgia Tech and two seasons of summer leagues in between, Lodise has over 1,000 plate appearances on his Baseball-Reference.com page before anything White Sox-related. He believes that experiences has prepared him to a degree that his physical development has yet to fully reveal.

"It allowed me to get at-bats and fail, because I think the biggest thing guys are scared of early on is failing," Lodise said. "I've had a lot of time to learn, and to fail, and to struggle and all those things. Having thousands of at-bats before I even hit the professional stage, it's really important. I've gotten to see a lot of arms, I've gotten to see a lot of shapes. I've not encountered anything that I haven't seen before yet."