In the time since Rickey Henderson's death was announced on Saturday, I've spent a lot of that time reading obituaries, memorials, tributes and personal histories, and relearning how much Henderson once wasn't revered, particularly during his time with the Yankees in the mid-1980s.

I know I've read about that over the years, but my brain never retains the details. It probably rejects them due to incongruity, because on the timeline that I became aware of Rickey, he was impossible to dislike.

My radar picked him up a couple of seasons later with the Bash Brother A's, which was the team that drew me to baseball on TV. As a 7-year-old, I had no reason to know or care about the contract squabbles, accusations of malingering or the polarizing effects of his hotdogging. I merely saw a guy whose strike zone was as big as mine, who wore sweet, bright neon-green batting gloves, and who rewarded the cameras for staying on him. Baseball is designed to withhold the easiest possible payoff because the best hitters come to the plate with the same regularity as the worst hitters, but Rickey came closer than any other player to guaranteeing action.

(Early 2000s Barry Bonds is the only comparable force, but while he surpassed everybody who ever graced the earth as a hitter, the unfathomable amount of intentional walks killed the buzz, because late-30s Bonds largely stayed in place and required other hitters to get him home. Rickey's walks thrilled because the movement was just getting started. When Hawk Harrelson called Henderson "the best offensive player I have ever seen" during the Year of Superlatives, this is probably what he was getting at.)

As my knowledge of baseball became more nuanced, Henderson remained fascinating. For how easily he blasted past Lou Brock's record for stolen bases, and more gradually ground his way to the all-time record for runs scored. For the position-player weirdness of batting righty and throwing lefty, and thinking about how much higher his OBP could have ticked with a step-and-a-half head start. For the way he traveled from team to team into his 40s, reaching base and running for whatever roster could use that specific skill set, and then continued playing independent ball when MLB teams had seen enough. For all the "Rickey" stories, verified and unverified. He was a great player to be a kid for, and unlike my favorite player of the era, Jose Canseco, Rickey was a great player to continuing learning about baseball through.

I feel like I'm running a risk of oversimplifying the experience due to the way nostalgia drives perceptions of quality. Back in May, the Washington Post ran a study about how, no matter how old you are, that family stability peaked before the age of 10, the cast of "Saturday Night Live" was funniest when you were 13, and the best music came out when you were in high school. I'm sure this natural tendency informs some of my thinking here, as much as it compels me to pick fluorescent green batting gloves for curling whenever they're available.

But it says something about the enduring nature of his appeal that whether you're talking about the baserunner-friendly rule changes or the idea of the Golden At-Bat, Major League Baseball thinks its future lies in making the game look like the one Rickey Henderson played.

Anyway, here are a few stories that struck me for one reason for another.

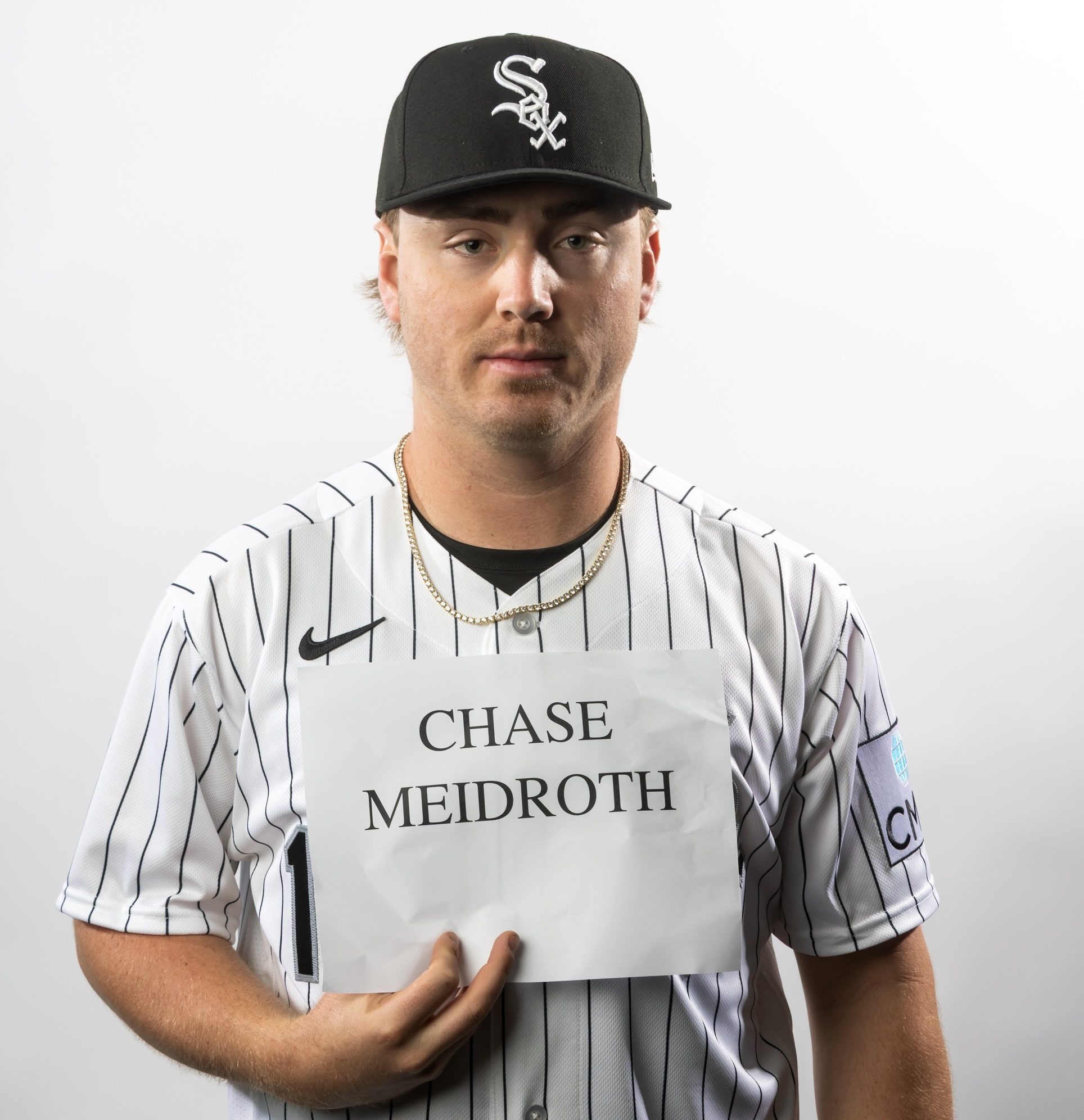

Howard Bryant wrote Rickey Henderson's biography, so his obituary is the first place to start. He goes into great detail about a fight with the White Sox that put Henderson and Tony La Russa at odds, at least until they united in Oakland.

I liked the kicker on Tyler Kepner's tribute:

Now the A’s are gone, off to Las Vegas by way of Sacramento, and Henderson is gone, too. Wednesday will mark 66 years since his birth, on Christmas night 1958 in the backseat of an Oldsmobile on the way to a hospital in Chicago. He was a man on the move from the very start.

Steven Goldman approaches Henderson's career from somebody whose youth included Henderson's controversial Yankee days. He suggests that while Henderson's reputation for detached, airheaded comments was at least somewhat earned in real time, the fact that he played in 3,081 MLB games invites the question of how much of his success was predicated on operating at a remove, so that the game couldn't wear him down physically or emotionally.