The family of the late Dick Allen is inviting media to attend a watch party for Sunday's reveal of the voting for the Classic Baseball Era Ballot, as a 16-member committee will vote on the Hall of Fame qualifications of eight candidates whose most significant career impact came before 1980.

After falling one vote shy of induction in another committee vote in 2021, the family of the famed Phillies and White Sox slugger and 1972 AL MVP "is very optimistic that this will be Dick's year."

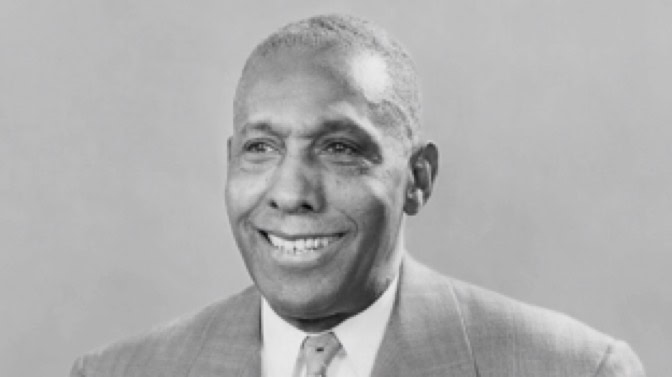

For supporters of legendary Negro League two-way player and trailblazing White Sox scout John Donaldson, after he earned votes from half of the 16-member panel three years prior (75 percent is required for induction), Sunday brings much more of a make-or-break feeling for his Hall of Fame candidacy.

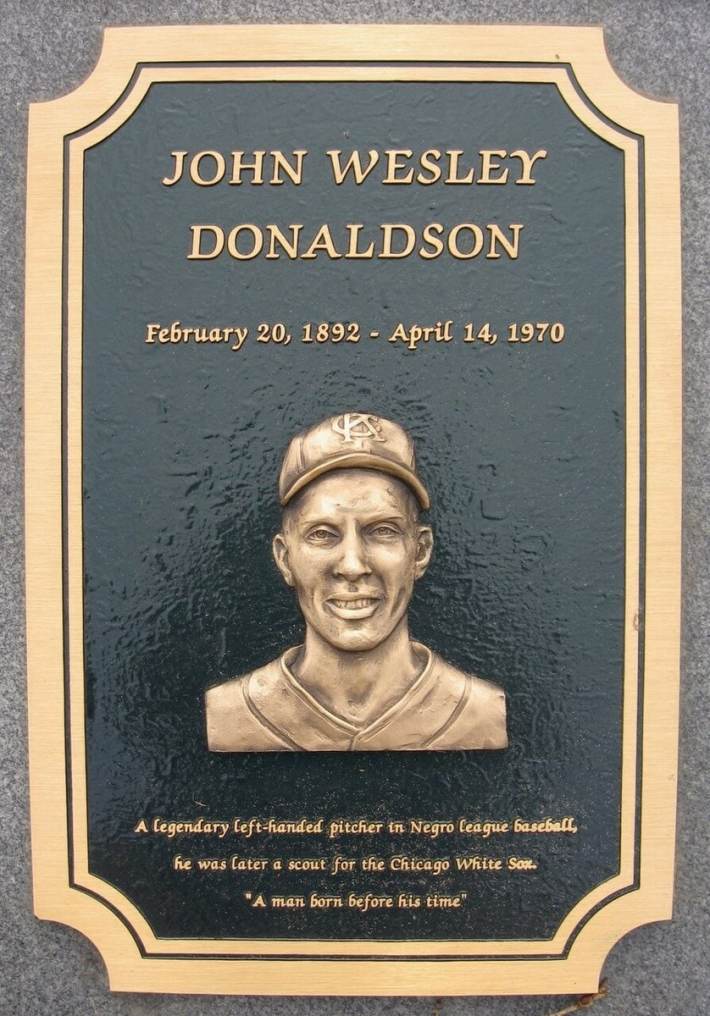

There's been a large push for recognition of Negro League players in the three years since Donaldson came up for a vote, from the concrete efforts for Negro League statistics to be recognized at the same level as Major League Baseball records, to the more ephemeral nature of a top Google result for a man that's been dead for over 50 years being a YouTube video about him being a playable character on MLB The Show. Some 20 years ago, Donaldson was lying in an unmarked grave at Burr Oak Cemetery in Alsip until Jeremy Krock of the Negro League Grave Marker Project enlisted the help of Jerry Reinsdorf and the White Sox to pay for a headstone worthy of his legacy. So it's tempting to hope this is a moment of unique momentum to secure Donaldson four more votes.

But there's another very possible scenario where Donaldson's support dips, more easily recalled and deserving players on the ballot like Allen, Luis Tiant and Dave Parker suck up all the oxygen, and the legendary left-hander's candidacy slips off the ballot in future meetings. Over the course of its history, the National Baseball Hall of Fame's attitude toward the contributions of Negro Leaguers has largely been one of reluctance, and the fear that the institution will prematurely conclude that this oversight has been addressed and move on is quite pervasive.

"I'm honored that he's even eligible, because I understand completely how this [could] never happen again," said Peter Gorton. "[The Hall of Fame doesn't] need to put Negro League baseball players into their institution, and it's completely their choice. If we don't like the taste of Diet Coke, we're not walking into Coca-Cola and saying, change your recipe. That's what the Hall of Fame is. It's a business. They decide, they decide the rules. They decide how that works. If you're going to sit around and just say that they stink all the time because of the decisions that they make, I don't think that's very productive to the legacies of Negro League baseball players."

For over 20 years now, Gorton has run The Donaldson Network; part informational website, part web forum community and part mission. From his home in Minnesota, Gorton and countless contributors have been sifting through old records and archived newspapers to compile a comprehensive collection of Donaldson's career accomplishments. Absent a plaque in Cooperstown, Donaldson has this digital shrine.

This community's work has built out a larger picture of Donaldson's career as an early 20th century barnstorming sensation whose appeal reliably drew large crowds even in cities that had never before hosted Black baseball, and ultimately played to fans in almost 800 different cities -- mostly across the midwest. His pitching exploits are on the scale of a tall tale, with Gorton confirming over 400 wins and greater than 5,000 strikeouts for the left-hander, figures which would likely be even larger in number if they weren't so stringent about their evidentiary standards. Beyond the details, the coverage of Donaldson clearly conveyed his superstar status.

"The people of John Donaldson's time knew that he was the greatest pitcher on the planet. The people of my time can't seem to believe that," Gorton said. "The fact is, I don't think John Donaldson's legacy needs the Hall of Fame as much as the Hall of Fame needs John Donaldson."

The research by Gorton and the Donaldson Network has greatly increased their subject's profile, and the Negro League historians on the Classic Baseball Era voting panel are drastically better equipped to argue his case to their colleagues than they were back when Donaldson was being considered in 2006. But the nature of this work is finding purpose in celebrating Donaldson's lifelong dedication to integrating the sport, and to see the value in proclaiming his historical importance, regardless of whether it will ever earn official recognition.

In keeping with his underdog status, MLB's effort to recognize Negro League statistics still largely rendered Donaldson's playing career to the sidelines. None of his playing career before 1920, when he was already 29, appears on Baseball Reference. Despite published accounts of thousands of games he pitched, only 22 appearances for the Kansas City Monarchs are officially attributed to his history as a major league player, as so much of his work existed outside the bounds of a formalized league. For someone who went through such great pains to document Donaldson's accomplishments, this is particularly noisome to Gorton, who says that discounting how much of the left-hander's career was spent playing showcases and exhibitions to make a living is affirming the segregation that kept him out of well-established professional leagues during his life.

Such excursions helped build a market for Black baseball, drew in enough revenue to fund teams and keep venues open, and were part and parcel with Donaldson's work to integrate the sport. And if there was wide understanding of how critical Donaldson was to the integration effort for professional sports in this country, Gorton doesn't think his post-playing career as a White Sox scout would be such a throwaway mention, even if he never quite sold his superiors on signing a teenage Willie Mays, or that his initial efforts to get teams to seriously scout Black American amateur talent often fell upon unsympathetic ears.

"It's written in newspapers that John Donaldson is attending White Sox team meetings," Gorton said. "He's the first Black face to ever walk into one of those things in the history of the game. They might have had Black scouts who bird-dogged guys saying they were really good. But they never put them on the staff and brought him into the meetings. They never did that, and John Donaldson stands alone as being the guy who crossed that barrier."

Donaldson did sign star Negro League catcher Sam Hairston to the White Sox, patriarch to the famed Hairston baseball family, only to see the first Black American player in franchise history mostly relegated to being a minor league legend as the big league club refused to make room for him on the roster. Few men have a more fitting epitaph than Donaldson's "A man before his time," and it correlates to his life's work being spent fighting the initial battles that eventually built out opportunities for others to build up more obvious Hall of Fame resumes.

To research the fight for racial equity in this country is to understand that its history exists outside the bounds of the stories that official institutions are willing to tell about themselves. The White Sox have encouraged and facilitated stories about Donaldson and Hairston so that the fan base can understand their importance in franchise history, but largely, MLB and the Hall of Fame have not been the most reliable sources for appreciating stars of the Negro Leagues.

Donaldson has been no exception. But none of his supporters, least of all Gorton, would be opposed to the Classical Baseball Era committee surprising a lot of people on Sunday by trying to make him one.