Jerry Reinsdorf is all but invisible to fans. He only addresses local media when it comes to universally good news. Anything more nuanced than "I'm happy Harold Baines made the Hall of Fame" he saves for an alma mater or Bob Nightengale, but even those interviews are few and far between. Expecting more is a fool's errand.

When it comes to the George Floyd protests sweeping the nation, it's not surprising that he and the White Sox have largely removed themselves from the discourse, but it's disappointing. The club's only official acknowledgment of the protests is this flaccid statement that offers no sense of place or time.

There's no mention of George Floyd dying at the hands of police, much less the deaths of Breonna Taylor or Ahmaud Arbery, the two other recent high-profile cases of police brutality and extrajudicial killings that have inspired the nationwide unrest. That image could have been deployed at any moment of tension over the last decade, or maybe just the third Monday of any January.

The team's next statement took the form of Rick Renteria wishing Guaranteed Rate a happy birthday. Because he mentioned "20th birthday," one can at least know what year it was said.

The Cubs issued a more thorough statement in support of African-Americans. Gushers beat them both, and Gushers is a fruit snack.

On one hand, the White Sox's silence has been baffling. Diversity is a big part of the White Sox's identity and pride. The crowds at 35th and Shields are notably different from those across town. White Sox Charities gets out into the neighborhoods. The club's Amateur City Elite program should be worthy of emulation by every MLB franchise, and it'll get another round of plaudits when some team drafts Ed Howard on Wednesday. Its executive vice president is Kenny Williams, who often has to speak about institutionalized racism from his role of one of the only African-American executives in the game. He spoke about it just late last month after the death of Bob Watson:

“One thing Bob and I talked about pretty regularly was the need for us to succeed in our roles, thinking that our success in those roles would have people look at us in a different way and maybe take a chance on the next guy who looked like us. For a while that looked like it may be the case, but it hasn’t turned out that way.”

The team's logo carries weight beyond baseball thanks to African-American arts. I've seen White Sox caps for sale among unrelated items on the shelves of urban streetwear stores in Seoul, Paris and Reykjavik thanks to hip-hop's propulsion, not because Paul Konerko is huge in Iceland.

Culturally, the White Sox don't have much reason to be timid.

Geographically, it's a different story.

* * * * * * * * *

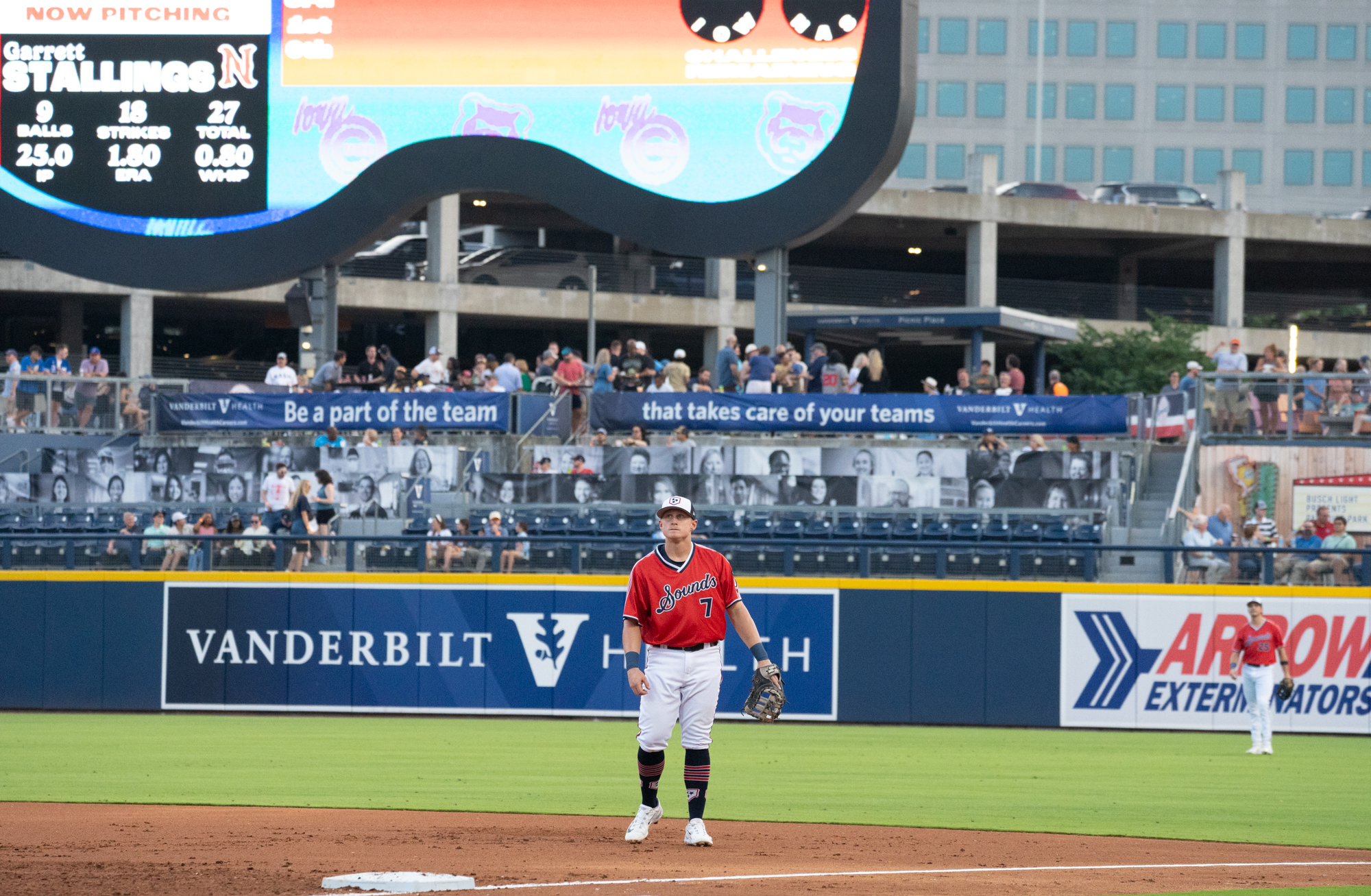

You know what is also a big part of the White Sox? Police. Granted, they're a big part of every team, in that current and former police often comprise stadium security. For instance, it might've seemed like a no-brainer for the University of Minnesota to end its contracts with the Minneapolis Police Department in the wake of George Floyd's killing, but the school took on significant risk in doing so.

But the White Sox have stronger natural ties still. Bridgeport is long considered the seat of Chicago authorities -- cops, firefighters and Daleys. There's a police precinct on 35th Street just a couple of blocks away. The White Sox host a game between police and fire departments every year.

The neighborhood's history with African-Americans is not a welcoming one. Before the Dan Ryan was the backdrop for new Comiskey Park, it served as a physical barrier between Armour Square/Bridgeport and largely black Bronzeville by design. While the neighborhood demographics have changed over the last couple of decades, African-Americans are still a distinct minority, and reminders of the area's uglier history have flared up during the protests.

This Block Club Chicago article includes white vigilante action at 31st and Princeton, and another incident 26th and Shields. This Chicago Tribune article references the former, and adds another scene on West Pershing Road.

And in the middle of that map, Guaranteed Rate Field was a staging ground for the Illinois National Guard.

That image isn't as shocking as it could be, just like Tim Anderson wearing a Sox jacket alongside "ACAB" graffiti has a certain historical resonance that other teams don't possess.

* * * * * * * * *

These two major facets of the White Sox's identity are in direct and open conflict, and the organization is acting as though it'd rather not pick a side. It fits right in with Reinsdorf's history of political donations. It's also a decision that looks far more cynical than pragmatic as the protests gain traction in ways and areas that few thought possible. Moore's reference to Bridgeport as a sunset neighborhood came to mind when seeing this Black Lives Matter protest from a notorious Texas sundown town:

If you only want to compare it to athletics, the University of Minnesota's decision to sever security ties looks less risky now that the city council is moving to dismantle the police department. One NFL employee went rogue and worked with players to create a viral video demanding a stronger league action, and Roger Goodell responded by recording a video in which he supported Black Lives Matter and admitted the league's previous stance on peaceful protests was a mistake. The CrossFit world is crumbling. Hell, Major League Baseball's tepid statement was even lapped by NASCAR of all sports.

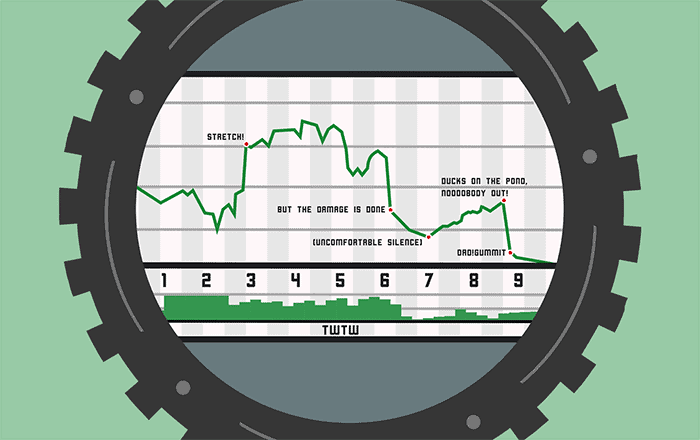

The longer this goes on, the more the White Sox's absence of courage stands out. They're almost lucky that fans won't be able to attend games in 2020, because who knows what direction that diverse gathering of thousands at the ballpark would take (Aug. 27 would've been this year's edition of the annual Police & Fire Night).

But I don't think you can separate the protests from the coronavirus. The pandemic has disproportionately affected African-Americans in terms of the virus' death toll, its economic impact, and even their ability to vote. It all works in concert to show that there's a raw deal for black people in the United States around every corner, which helps explain why Floyd's death broke the seal on an unfathomable amount of anger. That police around the country responded with that toxic combination of recorded excessive force and debunkable lies made that anger easier than ever for white people to comprehend.

Some members of the White Sox, like Anderson and Lucas Giolito, have taken it all in and feel compelled to speak out. The White Sox really aren't providing them cover. At best, it can be seen as hoping it all goes away. At worst ... are the Sox just waiting to side with the winner?

The White Sox probably don't see themselves that callously, but clinging to the status quo can always be defended in real time. Those real-time decisions also tend to embarrass institutions in hindsight. The White Sox can comfortably quote Martin Luther King Jr. as a quick salve now, but they probably won't want to relay what King said about Chicago in 1966, even if those quotes are equally relevant as groups of mostly white men with bats roam the streets near where the White Sox play.

Acting for justice is a lot less safe at the time it has a chance to make a difference. Parts of the White Sox have it in them to lead, but that just makes it harder to excuse the other parts of the White Sox that hold them back.